Tag: Research

Hans Haacke and Sarah Kleinman in Conversation

“Hans Haacke and Sarah Kleinman in Conversation” coincided with the opening reception of Hans Haacke’s exhibition, Dreams that Money Can Buy (Update), on view from September 30 to December 16, 2016 at the Maier Museum at Randolph College in Lynchburg, Virginia. Our conversation is prefaced by my ten minute introduction to Mr. Haacke’s work, which is the subject of my 2016 MA Qualifying Paper.

The Context

I began my investigation of Hans Haacke’s work in Robert Hobbs‘ spring 2015 graduate seminar, Conceptual Art. Haacke’s research-driven approach, criticality of the establishment, and his German heritage compelled me to delve into his oeuvre. In January 2016, I received a VCUarts Graduate Research Grant to conduct fieldwork and archival research at the Giardini della Biennale in Venice and the Historical Archives of Contemporary Art (ASAC) in Porto Marghera, Italy.

To obtain access to the Giardini and the German Pavilion, which are closed to the public from November until the Biennale opens in early March, I contacted Germany’s Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen (Institute for Foreign Cultural Relations) (IFA) and the Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit (The Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building, and Nuclear Safety) (BMUB), the agencies that fund and administer the pavilion. The managing architect of the pavilion granted me free reign of the site, including the roof.

From January 10 to 20, 2016, I explored the City of Venice and documented every archival document in the German Pavilion files, focusing on the years 1933 to 1948, coinciding with the rise of the Third Reich and Hitler’s dictum to renovate the pavilion to emulate the ascetic architectural language of National Socialism, and from 1991 to 1993, when the recently reunified Federal Republic of Germany planned its first post-Cold War biennale. Though I found an abundance of documents pertaining to the 1937-38 renovation of the pavilion, Haacke had left little trace of his own archival research.

With little substance on which to base my analysis of Haacke’s installation (aside from extant scholarship), I contacted the artist in March 2016 to see if he might be available and willing to discuss the installation. Our meeting took place on Thursday, May 26, 2016 at Haacke’s New York studio. As we wrapped up the interview, Haacke asked if I was familiar with a small university museum in Lynchburg. At the time, I was not acquainted with the Maier, though that would soon change.

In August 2016, the Maier’s curator of education learned about my research and invited me to present a lecture on the artist’s 50-year career. Two weeks before the opening reception, Mr. Haacke arranged to visit Lynchburg to install his work. This serendipitous series of events represents a significant point in my MA research and in my career.

In effort to respect Mr. Haacke’s request not to circulate his image online and in the media, the video of our conversation is available only via password. Please contact me directly at kleinmanse@vcu.edu to inquire about accessing the video.

Press from the event is available at The Burgh.

Protected: 49’53” (hommage à John Cage)

Research as Art and Art as Research (Final Project Narrative – May 1, 2017)

Preface

When I enrolled in the VCUarts graduate seminar PAPR 591 Beyond the Gap: Art into Life in spring 2017, I was determined to investigate the work of the late Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) curator Kynaston McShine, who had organized Information (1970). As the first critical survey in America of conceptual art, this exhibition resonated with a number of themes and topics in the seminar: institutional critique, participatory art, street art, artist collectives, and protest groups. To me, McShine represented a central figure in enabling the polemics of everyday life to erode the museum’s apolitical guise. From this, I assigned myself the task of scouring over 8,010 documents that I had collected from the archives of the Museum of Modern Art and the Jewish Museum in New York, an idea that I return to below.

During the final four weeks of the semester, I realized that writing and presenting a prototypical art historical paper would (a) be absolutely banal, falling squarely in the rubric of art discourse and (b) uphold the expectations that we [my peers in Beyond the Gap] have mutually constructed regarding the idea of who I am: Sarah Edith Kleinman, the art historian and PhD candidate. After experiencing my classmates’ projects, I realized that resorting to my comfort zone would be an injustice to the central premise of the course. In this respect, Nato Thompson’s stinging evaluation of Ben Davis’s essay, “A Critique of Social Practice Art,” applies to my initial project proposal: “a tautology that sets up the conditions for its own failure” [1]. In sum, my initial plan hindered the deeper project of probing the myriad ways a work, effort/labor, or a combination thereof might collapse art and life.

How does art intersect with my life?

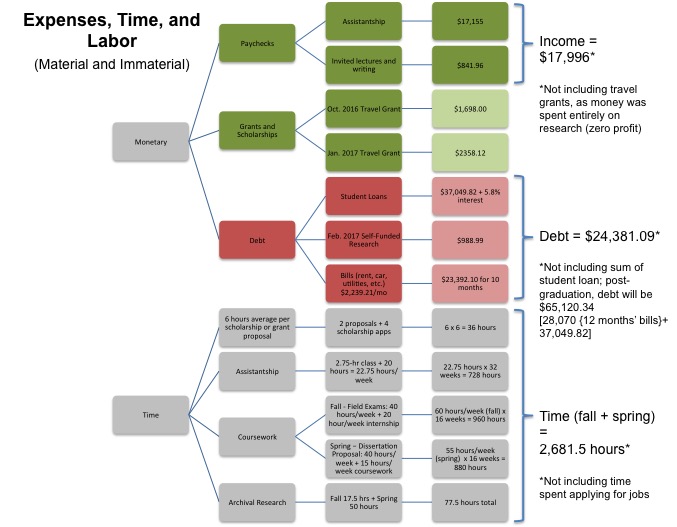

For the past 1,355 days, I have earned my living as a graduate teaching assistant in the Department of Art History. Coinciding with my assistantship, I have received full financial support and travel grants to pursue my MA and the first year of my PhD. When my teaching assistantship concludes on May 20, 2017, I will have spent 1,374 days engaging in and contributing to art historical discourse; from this, 278 days constitute PhD research. In effort to make sense of this journey and to work through my overwhelming anxiety about the looming prospect of joblessness, I began questioning the ways I might be able to instantiate some predictability and order in one of the most significant parts of my life: my dissertation research. From this idea, I created 49’53” (hommage à John Cage), a video capturing me scrolling through each document that I have reviewed from MoMA and the Jewish Museum during three research trips (October 18 to 22, 2016; January 4 to 13, 2017; February 16 and 17, 2017). Ancillary to 49’53” is a table of calculations of my income, grant and scholarship money, and expenses incurred during my archival research, entitled Tabulation of Expenses (Material and Immaterial) and Tabulation of Expenses (Time).

This blog, http://www.researchasartblog.wordpress.com, serves as the home for my video piece, tabulations of expenses, and this essay, which I presented the evening of Monday, May 1 as my final project for PAPR 591 Beyond the Gap: Art Into Life. Not only has this course been significantly challenging for me as an art historian, it is also the last class I will take in my educational career. The blog format provides ample room to continue expanding on this project, thereby resisting the modernist urge to produce a closed or completed object. For me, this project serves as a methodical and therapeutic means of attempting to understand the past 252 days, while providing space to continue documenting the work and labor associated with my research. In lieu of an art historical analysis typical of the person I was upon entering Beyond the Gap: Art Into Life, I intend for this project to be open-ended and to prompt conversation about aspects of art historical research as a practice.

An Idea

As I scrolled through my archival documents, my right index finger pulsing the arrow key, my eyes rapidly scanning each page for a pattern, a concept, an idea, or personality that I could relate to, I slipped into a familiar mental state that I call dissociative presentness, wherein the knots and blocks in my thoughts begin to loosen, allowing me to disentangle from the complexity I so often inject into my work. In this dissociative presentness, my sensory experience took over. I glimpsed down at my finger, still tapping the right arrow key. The staccato, atonal rhythm of the tap-tap-tapping and the corresponding progression of documents became a repetitive, thoughtless, yet meditative exercise. In a nod to John Cage and his movement entitled 4’33”, a statement about sound by the very absence of it, my project reverts the traditional role of an art historian. Here, archival documentation is presented as-is, without providing explicit historical narratives or inserting carefully crafted interpretations of the material.

Performing the Archives (On-Site and At Home)

How might we discuss the scope and volume of material that I procured? How does the act of scrolling quickly through personal correspondence—one of the most intimate forms of documented communication—alter, albeit temporarily, our understandings of the archive? On the one hand, the handwritten letters, memoranda, ephemera from the Primary Structures (1966) and Information (1970) exhibitions, plane tickets, exhibition catalogues, exhibition checklists, and price lists passing before my eyes represent years of planning on behalf of McShine. On the other hand, these images represent a portion of the time, money, labor, and work that were necessary to complete my dissertation proposal. Because the archives were only open four hours per day, four days per week, I could only briefly appreciate and scour the documents for content that would become the foundation of my dissertation proposal. Since returning from New York, I have dedicated two hours each day to reviewing the archival materials. Setting aside this tedious, conscientious process, 49’53” (hommage à John Cage) compresses the time and duration of my on-site archival work. Moreover, documentary evidence of McShine’s 50-year career is effectively pressed into a movement[2] not exceeding a single hour. The tangles of handwriting, turns-of-phrases, and personalities within my homemade digital archive have become familiar. Moreover, the documents have acquired an indexical quality in my mind, becoming temporally and symbolically linked to my real-time experiences in the archives of the Museum of Modern Art and the Jewish Museum. For instance, I will always remember my first encounter with John Baldessari’s letters, particularly his frank suggestion that MoMA, the Whitney, and the Guggenheim should take turns sending birthday, Christmas, and Valentines’ day cards to artists. In Baldessari’s words, “there would possibly be happier artists as a result and maybe fewer suicides” [3]. In a different folder, I found a handful of Hans Haacke’s original ballots for MoMA Poll (1970) (one each in yellow, red, blue, and green). Much later, I discovered that McShine had used the ballots for quick notes and memos to his secretary (he tended to use the red ones).

Without Precedent

To my knowledge, the labor of art historical research has yet to be discussed in scholarly literature or in art-as-research [4]. Yet as artist Andrea Fraser explains, “all art and all art discourse invariably exists within, produces, and reproduces, performs or enacts structures or relationships that are inseparably phenomenological, social, economic, and psychological”[5]. During the past fifty years, artists have taken up the process and methods of academic research as impetus for works of art. My project takes an alternative approach by considering the ways research in the context of the University and museum archive might be understood as a form of contemporary art practice and a means of knowledge production. Most notably, it serves as a place to document my personal journey as I transition into full-time doctoral research, providing a window for friends, peers, colleagues, and family to follow the art of art historical research.

I would like to express my utmost gratitude to Hope Ginsburg and Lauren Ross for challenging me to think Beyond the Gap—beyond my dissertation research and outside of my comfort zone. This new avenue of inquiry would not have come to fruition without your steadfast encouragement and (for lack of better words) tough love. This project and blog are dedicated to Hope, Lauren, and to my peers: Adrian, Aidan, Clare, Fumi, Kate, Magdolene, Tracy, Travis, and Will.

Notes

[1] Nato Thompson, “Growing Dialogue: What is the Effectiveness of Socially Engaged Art?” In Ben Davis, Tom Finkelpearl, Deborah Fischer, Elizabeth Grady, et al., Public Servants: Art and the Crisis of the Common Good, Johanna Burton, Shannon Jackson, and Dominic Willsdon, eds. (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2016), 440.

[2] Here, the word “movement” refers to music, denoting a principal division of a longer musical work. See the Oxford English Dictionary, March 2017.

[3] John Baldessari, MoMA Exhibition files 934.2, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, NY.

[4] Art-as-research is a recent field of inquiry that argues that the methodical processes and frameworks of research itself should be understood as an artistic process that yields linguistic, textual, and visual objects. Unlike the finished artwork, research as art is an open-ended process. See Julian Klein, “What is artistic research?” Journal for Artistic Research (23 April 2017). http://www.jar-online.net/jar/what-is-artistic-research/.

[5] Andrea Fraser, “Speaking of the Social World…” Texte Zur Kunst no. 81 (March 2011): 151-157. https://www.textezurkunst.de/81/uber-die-soziale-welt-sprechen/.

Tabulation of Expenses (Material and Immaterial)

Tabulation of Expenses (Time)

24 hours in a day

x 7 days/week=

168 hours/week

x 16 weeks/semester=

2688 hours/per semester

x 2 semesters =

5376 hours total waking and sleeping hours

(fall and spring semesters)

2,681.5 hours of labor = x x = 49.879%

5,376 hours total 100

During the fall 2016 and spring 2017 semesters, 49.879% of my waking and sleeping time was spent conducting research, working on coursework, upholding my assistantship, and completing funding applications (excluding time spent traveling to and from New York; eating, sleeping, socializing, and conducting other day-to-day tasks).

Terms and Definitions

art n.1

I. Skill; its display, application or expression.

1. Skill in doing something, esp. as the result of knowledge or practice.

2. Skill in the practical application of the principles of a particular field of knowledge or learning; technical skill.

3. As a count noun.

a. A practical application of knowledge; (hence) something which can be achieved or understood by the employment of skill and knowledge;

b. A practical pursuit or trade of a skilled nature, a craft; an activity that can be achieved or mastered by the application of specialist skills; (also) any one of the useful arts.

artist n.

I. A person skilled in a practical art.

1.a. A person who pursues a craft or trade; a craftperson, an artisan.

A person skilled in a learned art

III. A person skilled in any of the fine arts; (now more generally) a person who practices any creative art in which accomplished execution is informed by imagination.

art historian n. a student of or expert in art history.

research n.

1. The act of searching carefully for or pursing a specified thing or person; an instance of this.

2. Systematic investigation or inquiry aimed at contributing to knowledge of a theory, topic, etc., by careful consideration, observation, or study of a subject. In later use also: original critical or scientific investigation carried out under the auspices of an academic or other institution.

b. Investigation undertaken in order to obtain material for a book, article, thesis, etc.; an instance of this.

c. The product of systematic investigation, presented in written (esp. published) form.

3. As an attribute of a person: the ability or inclination to carry out scholarly investigation; learning, academic achievement.

4. Music. An introductory passage, played on a piano or organ, which establishes the theme, harmony, etc. of the main piece. Obs. rare.

Oxford English Dictionary Online, 2016.

When is research artistic?

When is research artistic?

According to Julian Klein of the Institutional für künstlerisch Forschung in Berlin,

“Research is not artistic when or even only when it is carried out by artists (as helpful as their participation may often be) but rather earns the attributed “artistic” – no matter where, when or from whom it was undertaken – on its specific quality: the mode of artistic experience.”

In this way, research may be understood as an open-ended creation process, one that is incongruous with the finished art object.